Nutrition is training! Eating healthy food is one of the most fundamental ways we can interact with our environment – so let’s make the right choices!

People regularly have questions about their nutrition plan; what to do during training, in the build-up to a race, during and after. It’s not surprising, countless of textbooks are filled on this. Human bodies are complex, with all of our unique quirks and preferences on top of the huge number of things that impact upon our bodies every day – each of us will have our own needs.

This guide is designed to equip you with the tools and knowledge you need to be confident in your own nutrition plan. And yes, of course, we’ll provide a template that works for most people too!

Your training, nutrition, and recovery are the three pillars that will predict your race day performance. So, let’s talk nutrition!

The Fuel

There’s been lots of talk in recent years about fat burning, keto adaptation and other fringe nutrition strategies; they’re interesting but do not improve race results or lab testing and are notoriously difficult to maintain for long periods.

Also, even if you train using one of these strategies I strongly recommend you still rely on carbohydrates for race day and the build-up week.

So, we’re fuelling our muscles with carbohydrates.

You only need to know three things (1) what to do in the days before the race, (2) what to eat on race morning, and (3) what to eat and drink during the race to get your personal best.

You might think this is oversimplification but if you can get this right you’ll be ahead of the vast majority. Every training session is a chance to practice what you’re going to eat for the big day. That means working out what you’ll need to eat on race day and a bit of experimentation to find out what works best for you.

Good to Knows

What’s the course like? For instance, is there a big hill where you’ll find it harder to eat so you should take in food before and after?

What nutrition will be provided on course at the aid stations and what distance will you cover between them?? If you can find out then you can practice with it. If you know ahead of time that you don’t tolerate it then you can plan to carry more of your own choice fuel.

What about the weather? Will it be hot or cold? Your finishing time and calories expended will increase with significant heat or cold, particularly if you are not used to it. You might plan to carry more food.

Train Your Gut

Research is increasingly clear that carbohydrate intake is linked to better performance in what is called a ‘dose-response relationship‘. That means more carbs yield a better finishing result. But if you try to eat 2-3 energy bars every hour on race day without practicing, you risk putting your gut under stress and finding yourself in an embarrassing situation!

You spend so much time training your muscles, heart and lungs; when you also include your gut in the training programme you will perform better and reduce the risk of a GI problem that could end your race early.

How do I train my Gut?

Just as with your muscles, your gut can be prepared to handle what a marathon will throw at it. Start getting used to your race nutrition plan by practicing it in training as soon as your marathon training plan starts. That means eating as though it’s race day in all of your key sessions.

If you know what nutrition products will be given out at the race then you can try that, but many runners prefer to stick with what they know and trust.

We advise athletes do cyclical training of your GI systems just like with regular training plans – sometimes you back off, other times you really work at it.

Eating on Easy Days

On easier days when training is not focused on building speed or distance, feel free to experiment.

Some runners like to see how they can handle fat as a fuel source by reducing carbs during those sessions or running before breakfast. Your speed in these runs will be slow. The hope is these “fasted” runs will allow you to develop your ability to burn fat.

Why is that good? You’ll delay hitting the wall, and if you do hit it you’ll be able to maintain a faster pace. There’s also evidence that these training sessions boost other aspects of your endurance training.

Eating on Harder Days

On hard days when you train fast or work on your long runs, quality of the training is important. This is the perfect chance to train your gut to perform just like you will on race day.

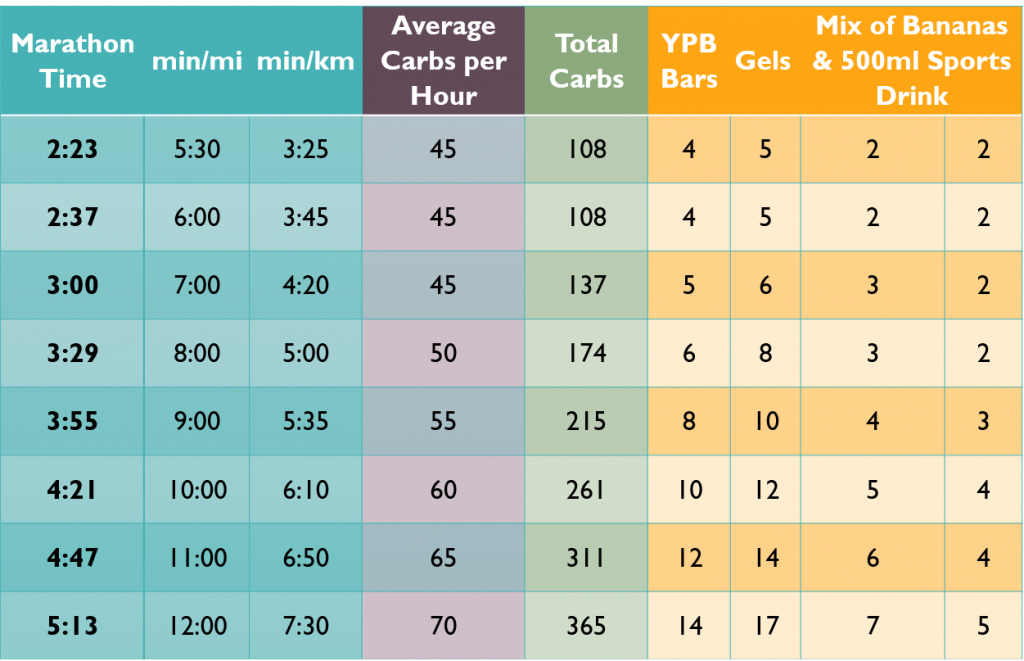

These are the days we try to work toward 60+ grams of carb per hour for sessions over 90mins. That’s approximately 1 YPB During bar every 25-30 minutes. For even longer sessions over 2.5 hours you might aim for as high as 80-90g/hour.

Some elite marathon runners will consume 75+grams of carb per hour. Look at the likes of the Tour de France carb intake.

Tip: You can only absorb more than 60g/hour of carb with a mix of carbs. With pure glucose, you max at 60g/hr. Check to see if your nutrition products have a mix of glucose and fructose like you will find in natural products like YPB bars.

You may not be able to tolerate that volume straight away, but your GI system will learn to deal with it over time. This is just like building up your long run. This is how elite level athletes can consume such large volumes of in races like the Tour de France – they had to work on it just like the rest of us.

Upset Stomach?

Each athlete has to work out that balance between GI comfort and the maximum amount of carbohydrate you can ingest. We all know those lucky people with iron stomachs, however some of us have a low threshold for stomach cramps.

Tip: Be flexible with your nutrition plan. If you feel like food and drink is pooling in your stomach, ease off the intensity and stop eating to allow your gut to catch up before hitting the gas again.

Carbohydrate Sources

Where can you get the fuel you need?

Among most brands: 1 bar = 1.5 gels = 5/6 chews

- 1 Banana 24-30 g

- 1 Gel 21-27 g

- Energy bar 20-40 g

- YPB During bar 27 g

- 4-5 Chews 16-25 g

- 500 mls of sports drink = 35 g

Can’t I just Eat When I’m Hungry?

Unlike fluid absorption, you will burn carbs faster than you can absorb them. If you wait till you’re starting to feel hungry or tired then your long run or race will have a bitter and shuffling end!

Early on, your gut is in prime condition to absorb carbs. Later in the race your stomach could refuse to take anything in. So, start eating from early in the run so you can finish strong.

Disregard this extremely well studied approach and your legs will let you know! This is one of the most common nutrition errors seen again and again in marathoners, ironman triathletes, and ultra-distance racers among other events. We also know that those who get it right finish fastest.

Carb-Loading

It’s a simple concept, you eat more carb-rich foods so that your muscles soak it up like a sponge giving you a fuel meter that’s fuller than it’s ever been!

It’s a simple concept, you eat more carb-rich foods so that your muscles soak it up like a sponge giving you a fuel meter that’s fuller than it’s ever been!

This doesn’t mean overeating, just prioritize carbs before salad and protein etc. Don’t leave this till the last meal the day before, you might still feel a heavy stomach in the morning and risk an upset stomach on the course.

Even though this should be a fun part of endurance races, research consistently shows that runners enter race morning with muscles that could have absorbed more carb. Carb-loading is a part of your race! Want to finish strong and avoid hitting the wall? Carb-load!

There’s no need to follow a complicated strategy for this – all the old strategies are equal in the lab. What’s important is that for about 3 days before the race you prioritize carbs in each meal and you aim for 10-13g/kg/day. Sample plans below.

If you’re travelling to your race, look up restaurants and menus before you get there. Many a race has been sabotaged by miles of wandering for a pasta place the night before a marathon!

Sample Meal Plan For the Day Before

Breakfast: a bowl of porridge topped with a banana, wholegrain toast or a bagel and a glass of orange juice

Lunch: a jacket potato and beans with salad

Dinner: a pasta starter, a chicken and vegetable main with brown rice, fruit salad and low-fat yoghurt

Snacks: bananas, crispbread, a handful of dried fruit, rice cakes

Breakfast Before Your Long Run / Race

This is down to personal preferences but it should be about 150grams of carbohydrate with little fibre. Whatever you’re used to eating before your long runs is probably what you should go for on race day. If you’re travelling to the race, pack your breakfast too.

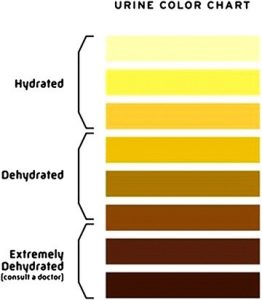

Aim for breakfast about 3-4 hours before the start and remember to get about 500mls of fluids in the 2 hours beforehand. Your urine should be pale, if it’s not then hydrate more before the run.

Need Your Coffee?

Caffeine and exercise performance has been a hot topic for decades. Does it help? Short answer, yes but not for everyone and side effects may not be worth it for some. About 3mg/kg (around 200mg for the average person) is enough for performance benefits.

Caffeine and exercise performance has been a hot topic for decades. Does it help? Short answer, yes but not for everyone and side effects may not be worth it for some. About 3mg/kg (around 200mg for the average person) is enough for performance benefits.

If you like coffee then a double espresso an hour before the race is about right for peak absorption. If you hate coffee then most caffeinated gels contain between 25-50mg of caffeine – you can take these in during the race for ongoing benefit.

Do NOT exceed 400mg of caffeine in a day.

Waiting for the Start

The hour before the race starts is usually when you see people anxiously bouncing on their toes, queuing for the toilet, trying to stay out of the wind/rain, or when us mortals watch the lean and sinewy runners warming up with some strides in tiny singlets!

During all this, you should be sipping about 200mls of fluids, and about 20 minutes before the start try to get another 20-25 grams of carbs (in your drink, gel, bar etc.).

During the Long Run / Race

Let’s keep this easy: drink to thirst and eat what you ate during your specific race pace long runs. Easy!

If you don’t remember what that was then aim for about 1 typical sports bar every 30 minutes or 1 gel every 20 minutes.

Thirsty? Drink. Don’t overthink this or drink too much; if you’re not thirsty then you don’t need it. Humans have been doing this for a long time, thirst is a great indicator and will adjust with temperature, sweat rate etc.

How Much Carbohydrate Per Hour During Your Long Run / Marathon

After the Long Run / Marathon

If you just finished the marathon then relax and indulge! Then follow a reverse taper over the next 2-3 weeks.

If you just finished a long run then you need to refuel carbs and take in about 20-25g of protein immediately and again after 3 hours. Your protein can be a recovery bar, shake, two scrambled eggs, whatever you like. If you’re planning on running again in the next 24-36 hours then carbs are a priority and you need to eat within 30 minutes of finishing your run. Aim for about 100g of carbs.

Why Plan My Nutrition?

Here’s a quick thought experiment for you – how many hours do you think you’ve spent preparing for a marathon by race day?

Say it’s an average of 3-4 hours per week over 12-16 weeks, typical for a 3-5 hour finishing time. That’s somewhere around 50 hours of running! Yet how much time do any of us give to preparing or planning our training and race nutrition? If you’re like most athletes I’ve asked, it ranges from no preparation at all to maybe asking a friend who’s done a marathon for a few tips.

If you can spare 10 minutes to read this guide and another 10 minutes each week to plan out your training nutrition for each session, then you can nail your marathon!

If you want to make this even easier, you can subscribe to YPB for personalized nutrition packages sent to your door.

Checklist

- Train with your race nutrition plan every chance you get! Your goal is to be able to tolerate 60+ grams of carbohydrate per hour at race intensity.

- Practice your breakfast plan before your long run. Find out what works for you.

- Look at the course route map and the nutrition at aid stations; know what’s available so you can practice with it.

- Plan your dinner the night before at a place that you know is good. Don’t wait till the last moment.

- Have all your race nutrition purchased and counted, don’t wait for the race expo.

3 Days To Go

- Carbo-loading begins: replace protein and salads in your meals with carb-rich foods.

- If you have a sensitive stomach, reduce fibre intake with 48 hours to go.

Breakfast

- Same as you had on long run days, eat 3-4 hours before the scheduled race start.

- Aim for about 150 grams of carbohydrate.

- Is your urine pale? Drink 200-500mls of fluid in the 2 hours before race start depending.

1 Hour To Go

- Your race nutrition is almost finished if you’ve carb-loaded and had a good breakfast

- Now, get a gel/bar/sports drink in with about 20-30 mins to go

During the Run

- This is the easy bit – do what you’ve practiced, whether that’s 30g of carb per hour for a runner following a slower and more relaxed intensity or 60+g/hour for the elites at high intensity.

- If you feel bloated, ease off the pace and stop eating and drinking until you start to settle then gradually get back on pace and plan

- Aim for 30-60 grams of carbs per hour.

- Drink to thirst unless you have worked out sweats rates and have a practiced hydration plan.

Congratulation!

We hope this helps with your training and race day! Remember – nutrition IS training!

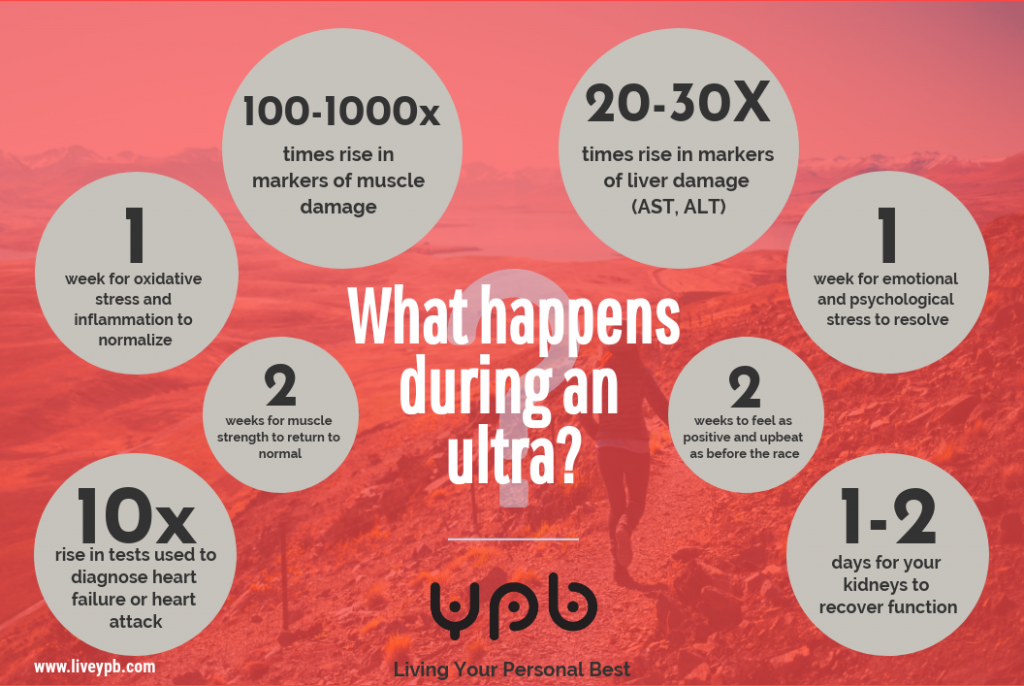

Can I do this,? What will happen when I start hurting? How am I going to respond when the suffering mounts? Do I have the mental fortitude to endure when all the signals from my body are begging me to stop?

Can I do this,? What will happen when I start hurting? How am I going to respond when the suffering mounts? Do I have the mental fortitude to endure when all the signals from my body are begging me to stop?

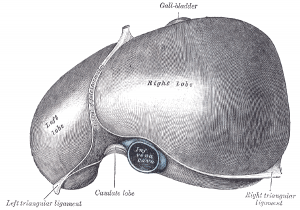

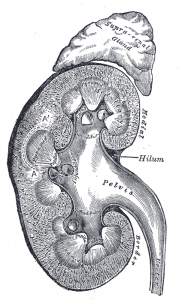

Wait! My liver isn’t doing any running, what’s going on there? Your liver sits in the upper right of your abdomen and it’s basically a very complex filter. It changes chemicals from one type to another. It gets first dibs on anything that comes into your bloodstream from your stomach to detoxify and make it safe for the rest of your body. Your liver also helps in metabolism, glycogen (carb) production, and hormone production among many other jobs.

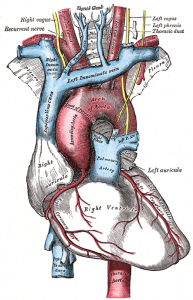

Wait! My liver isn’t doing any running, what’s going on there? Your liver sits in the upper right of your abdomen and it’s basically a very complex filter. It changes chemicals from one type to another. It gets first dibs on anything that comes into your bloodstream from your stomach to detoxify and make it safe for the rest of your body. Your liver also helps in metabolism, glycogen (carb) production, and hormone production among many other jobs.  This one isn’t a stretch of the imagination. Your heart is a muscular organ, muscles suffer strain when they work hard. Beating hard and fast for an entire ultra-distance event is a major challenge for your heart, and it shows.

This one isn’t a stretch of the imagination. Your heart is a muscular organ, muscles suffer strain when they work hard. Beating hard and fast for an entire ultra-distance event is a major challenge for your heart, and it shows.  It will come as no surprise that your kidneys get stressed out during prolonged exercise. You’re probably thinking this only matters if you don’t drink enough fluids – don’t be so sure!

It will come as no surprise that your kidneys get stressed out during prolonged exercise. You’re probably thinking this only matters if you don’t drink enough fluids – don’t be so sure!  Maybe you have a week-long stage race coming up and as well as everything else now you have to worry about damaging your DNA?!

Maybe you have a week-long stage race coming up and as well as everything else now you have to worry about damaging your DNA?!